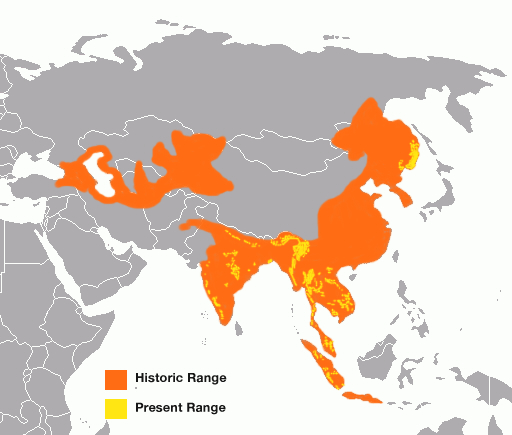

The Opportunity: Across their range, tigers face unrelenting pressures from poaching, retaliatory killings, and habitat loss. They are forced to compete for space with dense and often growing human populations. Tiger populations are declining in the face of massive poaching for illegal wildlife trade, habitat loss and fragmentation, and conflict with humans.

There were only about 3,200 tigers left in the wild in 2009 when this work was conducted with a goal to double that number by 2022, the next Year of the Tiger. Experts at the Kathmandu Global Tiger Workshop in 2009, stated that “without immediate, urgent, and transformative actions, wild tigers will disappear forever.”

Our Partners: The workshop was hosted by Nepal’s Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, and co-organized and co-sponsored by the CITES Secretariat, Global Tiger Forum, Global Tiger Initiative, Save The Tiger Fund, and the World Bank with delegates from 20 countries and representing numerous organizations including WWF.

The Journey: Advised the Global Tiger Workshop in Kathmandu, Nepal to define strategic actions to save the wild tiger from extinction including the longer-term change management efforts of this multi-stakeholder effort spanning 13 tiger range state countries and numerous global entities.

The Kathmandu Global Tiger Workshop was the first in a series of political negotiation meetings occurring throughout the year and leading up to a final Heads of State Tiger Summit in September 2010, which was the Year of the Tiger.

The workshop led to a process where more than 250 experts, scientists and government delegates from 13 tiger range countries called for immediate action to save tigers before the species disappears from the wild, citing the urgent need for increased protection against tiger poaching and trafficking in tiger parts in a lead up to the 2010 Year of the Tiger.

The Result: The recommendations from the process included support for implementing a resolution related to tigers in the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES), and to avoid financing development projects that adversely affect critical tiger habitats. The meeting was considered “a dramatic turning point for conserving this magnificent species, its habitats, Asian biodiversity, and the billions of people who depend upon healthy natural landscapes for which tigers are the talisman.”

The workshop led to a series of political negotiation meetings that occurred throughout the year and lead up to the final Heads of State Tiger Summit in September 2010, during the Year of the Tiger.

Other efforts resulting from the work included: enhancements to protecting core tiger habitats, partnering with communities to integrate conservation and development needs, cracking down on poaching and illegal wildlife trade and expanding conservation interventions to include corridors and habitats beyond existing protected areas. Over a decade later, it was seen that efforts initiated at the Kathmandu Global Tiger workshop supported the increase of Tigers in the wild from 3,200 to nearly 5,600 and in Nepal the wild tiger population is said to have nearly tripled in that time frame to 355 individuals according to National Tiger and Prey Survey in 2022.